Cross-Examination of a Police Officer

Cross-Examination of a Police Officer

Last week, I wrote about how the United States Constitution guarantees American citizens the right to due process of law, which includes the right to cross-examine witnesses who testify against them. I thought it would be worthwhile to show you how an effective cross-examination is conducted by an attorney.

Last week, I wrote about how the United States Constitution guarantees American citizens the right to due process of law, which includes the right to cross-examine witnesses who testify against them. I thought it would be worthwhile to show you how an effective cross-examination is conducted by an attorney.

While my law practice is currently focused on representing clients who have been injured as a result of someone else’s carelessness, during my early years of practicing law, some of my clients included people who had been charged with traffic and criminal offenses.

Below you will find part of a cross-examination that I prepared for a case that I had in the mid-90s. My client — I’ll call him Mr. Jones — was involved in an automobile accident that was his fault. The police officer who investigated the accident gave him some traffic tickets, one of which was for driving under the influence of alcohol. A Breathalyzer test was not administered to Mr. Jones.

The purpose of a cross-examination is to point out flaws in the testimony of an adverse witness and to discredit the witness in the eyes of the jury. There are two primary rules for cross-examination: the lawyer should (1) only ask leading questions, and (2) never ask a question that the lawyer doesn’t know the answer to.

A leading question is a question that is framed in a way that suggests the answer that the lawyer wants to obtain from the witness. A leading question is ordinarily structured so that only a yes or no answer is required. This allows the attorney to exercise control over the witness.

The opposite of a leading question is an open-ended question, which does not suggest an answer, but allows a witness to give an answer that is in the form of a narrative statement. Open-ended questions can be dangerous because witnesses are then allowed to testify to something that the lawyer may be unaware of and that may be harmful to the lawyer’s case.

Anyway, here are the questions and answers to part of my cross-examination of the investigating officer in the Jones case:

Q: Officer, you testified earlier that Mr. Jones told you that he had been drinking while he was driving, is that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: And in a case like this, you would consider that admission to be a very important fact, is that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: How long have you been a police officer?

A: I’ve been a police officer for 21 years.

Q: How many hours a week do you work?

A: 40.

Q: What shift?

A: 3rd shift.

Q: Officer, one of your duties as a police officer is to document incidents that you investigate and one way of documenting those incidents is to write a police report, is that correct?

A: Yes.

Q: As a matter of fact, when you were first trained as a police officer, you received training on how to write a police report, is that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: You learned through your training and experience that it is important to write up your police report within a short period of time after you investigate an incident so that the report is written while your memory is still fresh, is that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: Do you have any guidelines or requirements as to how soon a police report should be prepared after the investigation of an incident?

A: Yes, we’re required to finish all police reports before the end of our shift.

Q: Isn’t it true that one of the reasons you’re required to finish all your police reports before the end of your shift is because your memory is fresh at that time?

A: Yes.

Q: Isn’t is also true that if you don’t prepare a report within a short period of time after the incident, your memory of the facts of the incident may be affected by the fact that you will actually investigate several other incidents over the course of the next several days?

A: Yes, that is true.

Q: And isn’t it true that although you don’t put every single fact that occurred in a police report, you do put important facts that relate to the incident in the report?

A: Yes.

Q: Officer, you prepared a police report after you arrested my client, Mr. Jones, for a DUI, isn’t that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: In fact, you prepared the police report the same day that you arrested Mr. Jones, which was on January 1, 1996, isn’t that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: And you prepared your report within 24 hours after the incident, as required by your police department’s guidelines, isn’t that correct?

A: Yes.

Q: I’m handing you what’s been marked as Defendant’s Exhibit 1, which is a copy of your police report. Would you take a look at that for me?

A: Yes

Q: Is that the police report you prepared after you arrested Mr. Jones.

A: Yes.

Q: You indicated earlier in your testimony that Mr. Jones admitted to you that he had been drinking alcohol while he was driving, is that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: And you also testified that Mr. Jones’s admission to you that he had been drinking while he was driving was an important fact, is that correct?

A: Yes.

Q: Would you show me in your police report where you wrote down that Mr. Jones admitted to you that he had been drinking while he was driving.

A: It’s not in there.

Q: Officer, you prepared this police report over six months ago, isn’t that true?

A: Yes.

Q: Would you say that your memory was better within 24 hours of the incident when your police report was prepared, or would you say your memory is better now, more than six months after the incident?

A: Well, I would say my memory was better 24 hours after the incident.

Q: And yet, within 24 hours after the incident you did not write in your police report the important fact that Mr. Jones told you that he was drinking while he was driving, isn’t that correct?

A: Yes, that is correct.

Q: Officer, would you agree with me that the truth never changes?

A: Yes.

Q: Would you tell me then officer, which of your statements are the truth: the statements that you wrote in the police report within 24 hours of the incident, or the statements that you made in court today, more than six months after the incident.

A: I have told the truth all along.

Q: You would agree with me though that the truth never changes, wouldn’t you?

A: Yes.

Q: Would you also agree with me that once a set of events or circumstances has occurred, you cannot change that set of events or circumstances at a later time, would you agree with that.

A: Yes, I would agree with that.

Q: And yet, what you have testified to today, more than six months after the incident, is different from what you wrote in your police report right after the incident, is that correct?

A: No, that is not correct.

Q: It’s not? (Said somewhat sarcastically.)

A: No.

Q: That’s all I have, your honor.

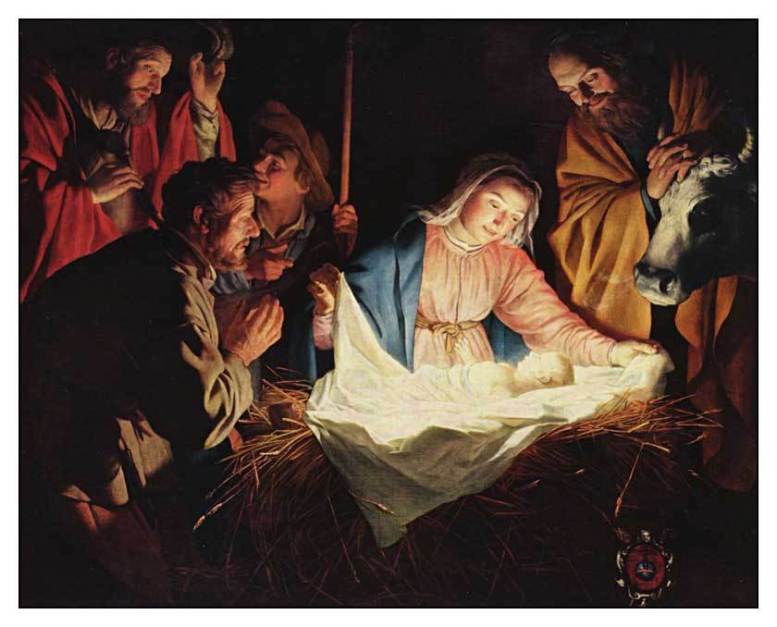

At the moment of your death, in a flash, your entire life — everything that you ever did — will instantly be revealed to you. You will be overwhelmed, in part, because you will feel as though you’ve been cross-examined by Almighty God. You will be completely aware of every sin of commission and omission that you ever committed. You will also be aware of every act of love and mercy that you performed throughout your lifetime. Will your sins outnumber your acts of love and mercy? Uh-oh. If you’re like me, you have a lot of catching up to do.

2 Comments

[…] to the tribunal, (4) advance notice of the evidence that the opposing party has against him, (5) the right to cross-examine adverse witnesses, (6) the right to have the final decision of the tribunal based exclusively on the evidence […]

Harry, your account on cross-examining above is fascinating to me. I am looking forward to the time when it will be Jesus who will be asking me the questions and helping me give Him the correct responses. You didn’t say how this was solved. I assume that the client was freed of guilt, since the officer’s report was faulty. Thank you once again for giving us, your readers, glimpses of your life as an attorney. with loving prayers for you and your family. Sister Roberta