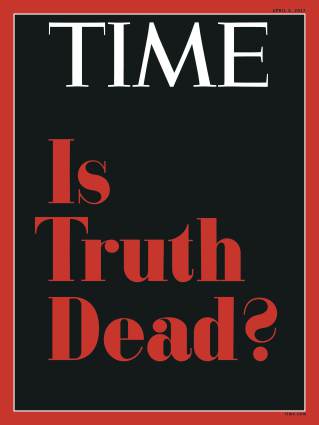

What is Truth?

What is Truth?

During the mid-1980s, I had a good friend — I’ll call him “James” — who I periodically had conversations with about life, politics, family, and religion. I was five years younger than James, and he was a lot smarter than I was. He breezed through elementary school, high school, and college, without any problems. He was quick to grasp new concepts and was a great problem solver.

During the mid-1980s, I had a good friend — I’ll call him “James” — who I periodically had conversations with about life, politics, family, and religion. I was five years younger than James, and he was a lot smarter than I was. He breezed through elementary school, high school, and college, without any problems. He was quick to grasp new concepts and was a great problem solver.

On one occasion, James and I got into a conversation about God. During that conversation, I learned that he had serious doubts about the existence of God. James had grown up in a devout Christian home. His family frequently attended church services, and all his family members and relatives had a strong faith and belief in God.

After a long discussion, I came to the conclusion that James had lost his faith during his high school and college years. He had come of age during the 1960s, when the sexual revolution in America was in full bloom. He didn’t like the teachings of his church concerning premarital sex and adultery. When I expressed to him that there were certain moral truths that were put into place by God to govern the behavior of man, he scoffed at me and declared that “there are no absolute truths.”

After further discussion, I realized that he had bought into the theory of relativism. The word “relativism” is defined as “a belief that there is no absolute truth, only the truths that a particular individual or culture happen to believe.” According to the theory of relativism, each individual determines in his or her own way what is moral and immoral.

The opposite of relativism is “absolutism,” which is defined as “the acceptance of or belief in absolute principles.”

When James declared to me that there were no absolute truths, I reminded him of a memorable event that occurred when we were young boys. I asked him if he remembered the event I was talking about. He remembered it very clearly. We discussed what we both remembered, and it was obvious that our memories were exactly the same.

After I established that our memories of the event were the same, I asked, “Are you sure that it happened that way?” When he said yes, I asked, “Are you absolutely sure that it happened that way?” He immediately sensed where I was going with my questioning and said, “Well, no, I’m not absolutely sure. Things could have actually happened a little differently than we both remember.”

I then asked, “Are you talking to me right now?” He answered, “Of course I am.” Then I asked, “Are you absolutely sure you’re talking to me right now?” He hesitated and then launched into an explanation as to how the conversation that we were having could be something that was occurring in our imaginations, which was apparently his way of supporting his belief that there were no absolute truths.

That conversation with James took place more than 30 years ago. At that time, I had three children and was busy trying to manage my growing law practice. James was single and was working for a local company. He eventually moved out of the area for a new job. After he moved, we only talked on the phone about once a year, and our conversations focused on catching up on what was new in our lives.

While I continued to have more children and expand my law practice, James went from job to job and from one relationship to another. It was as though he was lost without a compass. His life had no direction. I felt sorry for him.

I knew what his problem was. While my life was governed by certain absolute principles that had been instilled within me by my parents, grandparents, relatives, and elementary schoolteachers, his life was governed by feeling-based “values” that changed with the wind. He had trouble maintaining long-term, loving relationships with his girlfriends, and he also struggled to function normally in society.

I was very fortunate because I was born on the dividing line between what was then known as a virtue-based society and what would later become a narcissistic-based society.

The definition of “narcissistic” is “extremely self-centered with an exaggerated sense of self-importance, marked by or characteristic of excessive admiration of or infatuation with oneself.”

While the theory of relativism had been around for a while, it flourished during the sexual revolution of the 1960s, when many teenagers and college-age individuals threw caution to the wind and abandoned the virtue-based principals of their parents and grandparents and adopted the self-centered “values” that gave them permission to satisfy their sexual desires without the necessity of making a lifetime commitment to their “lovers.”

Because I was born in 1957, I wasn’t old enough to get caught up in the first sexually permissive tidal wave that swept through our country during the 1960s. My friend James wasn’t as fortunate as I was. He was seduced by the self-serving belief that he had the right to develop and adopt his own “truths” — truths that would allow him to satisfy his own desires and indulge in whatever moral depravity that he determined was acceptable.

By adopting this new belief system, James ignored what the great Greek philosopher, Aristotle, had written more than 2,300 years earlier — that for humans to properly function, they have to learn and put into practice virtues that will lead them to make wise decisions and engage in acceptable behavior.

For thousands of years, societies that adhered to the virtuous standards of behavior that Aristotle wrote about functioned well and got along with each other. Societies that abandoned those virtuous standards of behavior and adopted their own self-centered, self-serving beliefs as appropriate standards of behavior either ended up collapsing or at war with each other.

So where are we at right now in our society? Unfortunately, we have an ever-increasing number of individuals who have become extremely self-centered with an exaggerated sense of self-importance and an excessive admiration and infatuation with themselves. They have become so narcissistic and power hungry that they are now demanding that you and I approve, adopt, and abide by their sadistic and perverted beliefs — beliefs that they have turned into their own “absolute truths.”

To be continued.